This exhibition presents new ways in which sound, and by extension, communication and language, can be experienced.

Sounds Assembling: Communication and the Art of Noise presents new ways in which sound, and by extension, communication and language, can be experienced. A variety of works by artists—many from this area—explore the nature of sound and other ways of conveying and perceiving meaning.

London and Southwestern Ontario is home to a notable number of artists experimenting with sound. These include Leslie Putnam and David Bobier. Putnam’s I keep trying to tell you (2013) is an installation of handmade, pod-like forms imbedded with audio elements to create a vivid, shifting environment. Bobier’s Busy Hands (in conversation) (2013) presents unspoken forms of expression, such as culturally shared gestures and body language. Both artists also engage other sensations, in this exhibition, that of smell: the works involve the use of fragrant beeswax. For his part, Bobier often mixes it with spices or other materials to provide another type of sensoryexchange.

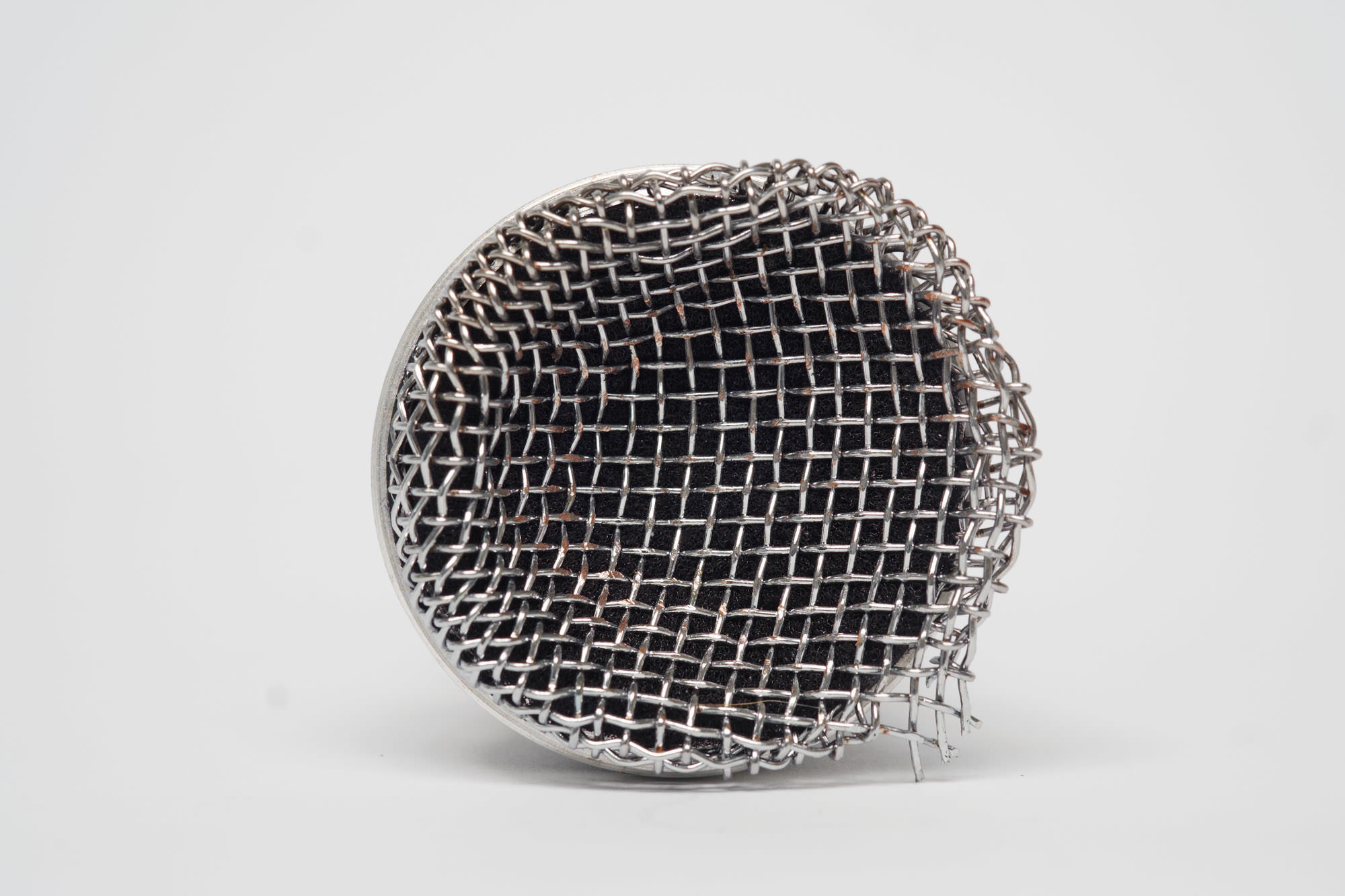

Christof Migone, Micro (Head) VI, 2014. inkjet print on paper, Image Courtesy the artist. Photo credit: Dimitri Levanoff

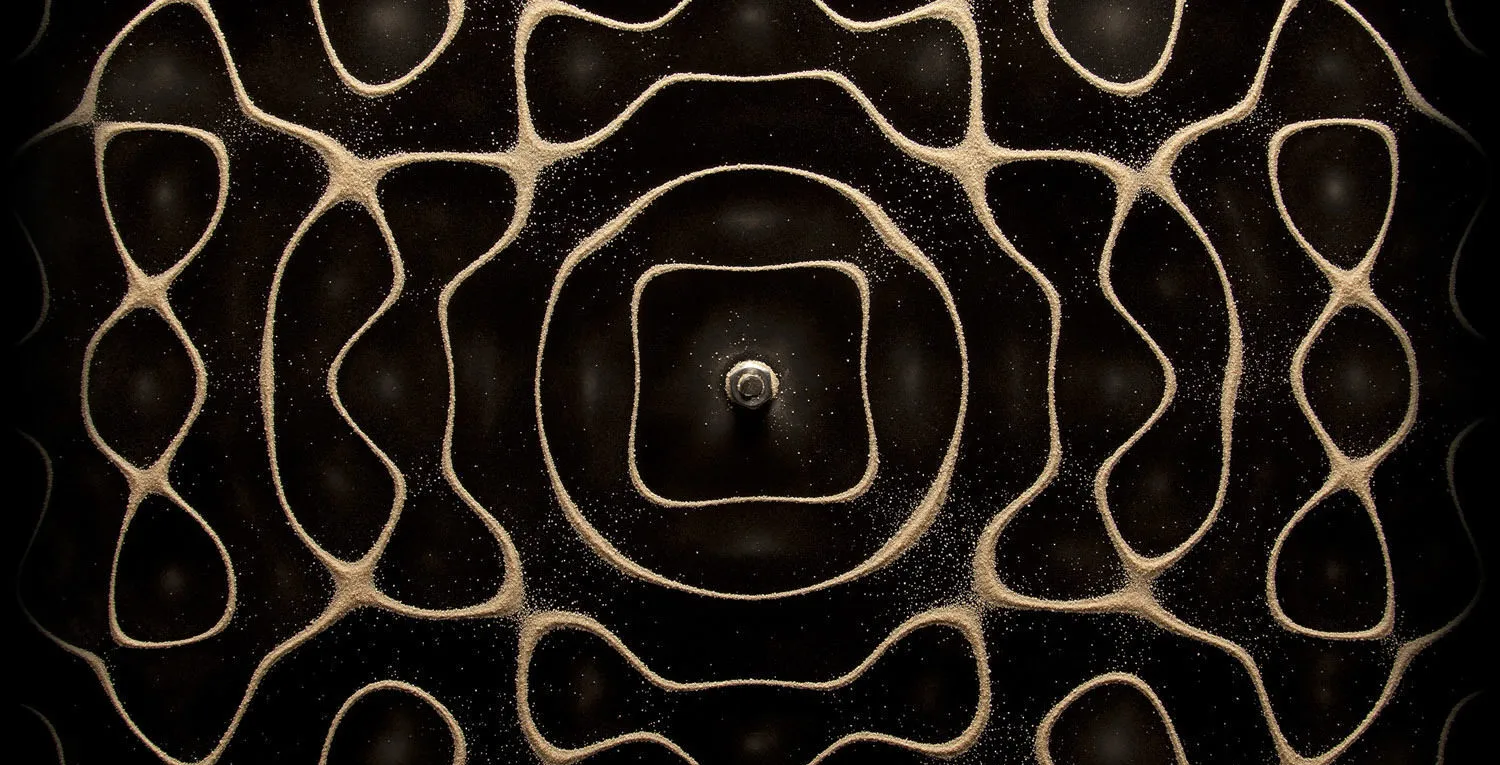

Other featured artists visualize sound and language. Older and more recent works by David Merritt reveal his ongoing interest in how meaning is conveyed. Talking Hole Burning (1993-98) and Aintnothin (2013) both depict the flow of language in inventive ways, here using audio, sculpturally-rendered script, and video. Barbara Steinman’s Tablets (2003) consists of glass panels bearing etched waveforms that correspond to vocalised words. Her treatment of terms such as Peace, War, Revenge, Love, and Violence give us “sound with presence, and presence without sound,” and her choice of words underlines the import of human interactions. In a related line of inquiry, Gary James Joynes (aka Clinker) also records the physicality of sound. In videos, prints and performances, he creates imagery through sound frequencies. Oscillating soundwaves vibrate fine particulate (such as sand) into mandala-like patterns, letting us “see” sound. Christof Migone also investigates sound and technology. Sounds Assembling features prints in his Micro (2014) series and Testing, Testing… (2016) which exists here as an installation and occasional performance piece. Both incorporate microphones, the real and potential applications of audio technology, and mediated sound. Kevin Curtis Norcross’ works (2017) documents other forms of auditory information, here in the form of hand-cranked musical devices which play notes corresponding to the noise of insects (specifically, the recorded movements of ash borers). His work involves player sheet music that transcribes the exit holes of emerald ash borers from ash trees. Marla Hlady’s kinetic sculpture humorously riffs on the emotional terrain of sound. Wah-wah teapot (landscape for Alvin Lucier) (2006) involves two moving teapots fitted with speakers, electronics and a microprocessor. An excerpt of a slide guitar can be heard through the teapots’ comically opening and closing lids, providing a visual, as well as aural, experience. Since the early 1980s, David Rokeby has created interactive sound installations where empty space is made reactive. Minimal Object (with time on your hands) (2012) explores the spatial presence of sound. In it, a seemingly neutral canvas reacts to the presence and movement of viewers by emitting a field of changing noises. In this way audition becomes a tactile experience.