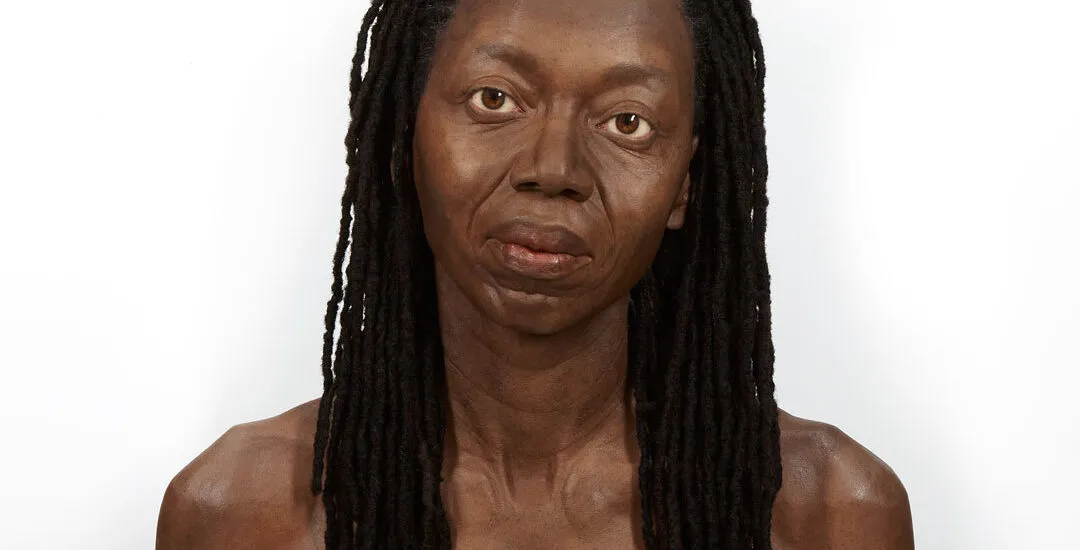

Penny is renowned for creating hyper-realist sculptures formed, forged, and filtered through digital photography.

Atrium, Main Level Our society is obsessed with the idea of the perfect image. Whether it’s the latest filter’s ability to morph our faces into algorithmic consumables for social media, or the reduction of pictures to digital information—pixels, MBs, and JPEGs—our understanding of image perfection is of a piece with the idea of image manipulation. Evan Penny is renowned for creating hyper-realist sculptures formed, forged, and filtered through digital photography. With Female Stretch, Variation #2, the Toronto-based artist’s attention to detail is undercut by an engineered distortion that makes the face not only hard to see, but hard to look at. This monumental three-dimensional portrait of an anonymous woman teeters between showing and stretching the truth. At first glance, Camille is conventionally representational. The bust’s perfection seems rooted in honest realism. The subject is Penny’s friend, the influential Jamaican-born Canadian media and performance artist Camille Turner. Yet, the abrupt, almost photographic, cropping of the figure, the object’s spatial ambiguity, coupled with the work’s uncanny life-sized scale, lends Camille a destabilizing presence. Evan Penny’s sculpture raises questions about perception in the digital age. Can Female Stretch, Variation #2, be both an accurate representation of something—or someone—and a misrepresentation of reality? Does Camille, through its exactitude, get us any closer to knowing the real Camille Turner? It is worth noting that Penny’s talents were embraced by Hollywood; in the 1990s, he designed prosthetics for the Oliver Stone films JFK, Nixon, and Natural Born Killers. Fact and fiction, Penny manifests digital manipulation in the tangible world. Image: Evan Penny (Canadian, b. 1953), Camille, 2014, pigmented platinum silicone with epoxy and glass fibre substrate, human hair, and UV-stable plastic eyes, Collection of Museum London, Gift of the artist, Toronto, Ontario, 2020